Truth Commission: Chile 90

Truth Commission: National Commission for Truth and Reconciliation

Duration: 1990 - 1991

Charter: Supreme Decree No. 355

Commissioners: 8

Report: Public report

Truth Commission: National Commission for Truth and Reconciliation (Comisión Nacional de Verdad y Reconciliación or the “Rettig Commission”)

Dates of Operation: May 1990 – February 1991 (9 months)

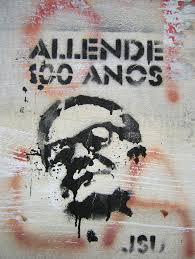

Background: In 1973, President Salvador Allende was removed from power and General Augusto Pinochet took over the Chilean government. Pinochet was accused of numerous acts of repression against opposition groups. The Pinochet dictatorship ended in 1989 when he conceded to holding elections and then lost to Patricio Aylwin by a narrow margin. Shortly thereafter, President Aylwin established Chile's National Commission for Truth and Reconciliation known as "the Rettig Commission" to investigate human rights abuses that occurred during the Pinochet regime.

Charter: Supreme Decree No. 355 (PDF-106KB), April 25, 1990, was issued by President Aylwin with the signatures of the Minister of the Interior and the Minister of Justice.

Mandate: The Rettig Commission was mandated to document human rights abuses resulting in death or disappearance during the years of military rule, from September 11, 1973 to March 11, 1990. Significantly, torture and other abuses that did not result in death were outside the scope of the commission’s mandate.

Commissioners and Structure: The Rettig Commission was comprised of eight commissioners, six men and two women. Commissioners were selected and named by President Aylwin in the Commission’s Decree. Former Senator Raúl Rettig chaired the commission.

Report: The commission released its report in February 1991, popularly known as the "Rettig Report".

- Full Report (11132KB-PDF)

- Part I (744KB-PDF)

- Part II (1021KB-PDF)

- Part III (8800KB-PDF)

- Part IV (690KB-PDF)

- Appendices (122-PDF)

Findings:

Conclusions

- The commission’s final report documented 3,428 cases of disappearance, killing, torture and kidnapping, including short accounts of nearly all victims whose stories it heard.

- Most of the forced disappearances committed by the government took place between 1974 and August 1977 as a planned and coordinated strategy of the government.

- The National Intelligence Directorate (DINA) was responsible for a significant amount of political repression during this period.

Recommendations

- The commission recommended the establishment of a National Corporation for Reparations and Reconciliation to provide continuing assistance to victims that testified. It suggested reparations should include symbolic measures as well as significant legal, financial, medical and administrative assistance.

- The commission recommended the adoption of human rights legislation, the creation of an ombudsman’s office and the strengthening of civilian authority in Chile's society and judiciary system.

Subsequent Developments:

Reforms

- Attacks by armed leftist groups against right-wing politicians, including the murder of right-wing leader Jaime Guzman, shortly after the release of the report halted planned efforts for reconciliation programs based on the report’s findings.

- The report was fully endorsed by President Aylwin. When presenting the report to the nation, he apologized to victims and their families on behalf of the state. Augusto Pinochet and the leaders of the armed forces rejected the findings of the report.

- In the beginning, Chile’s efforts at reform were hindered by the institutions loyal to former President Pinochet, in particular the military, the legislature and the judiciary. Eventually, the process initiated by the truth commission contributed enough momentum to start implementing state reforms. In 1998, the National Holiday, which celebrated the 1973 coup, was abolished. In 2005, a long constitutional reform process resulted in amendments that allow the president to fire the armed forces' commanders. The National Security Council, a military-dominated body, has been stripped of all but advisory powers.

- On August 12, 2003, Chilean President Ricardo Lagos appointed a second commission, the National Commission on Political Imprisonment and Torture, also known as the "Valech Commission" to document additional abuses, including torture, committed under the military dictatorship. The Valech Commission issued its report in November 2004.

Prosecutions

- The Pinochet regime passed an amnesty law, Decree Law 2191 (PDF-308KB) in 1978. President Aylwin’s incoming government was unable to repeal the law without a legislative majority. As of early 2009, the decree is still in force and its enforcement is left to the discretion of the courts.

- However, Augusto Pinochet was arrested in 1998 in Great Britain for violating international law. His arrest and prosecution has opened the door for the amnesties of other accused perpetrators to be challenged. Amnesty has been repealed in a few cases.

- Pinochet increasingly lost legitimacy with the Chilean conservative sector who still supported him when he was stripped of his parliamentary immunity in August 2000 by the Chilean Supreme Court, and indicted together with other military officers for their role in deaths following the 11 September 1973 coup. Multiple other indictments followed. In 2004, Pinochet was put under house arrest on charges of tax fraud, money laundering and enrichment from weapons traffic. He died in December 2006.

Reparations

- The Aylwin government established the "National Corporation for Reparation and Reconciliation" (enacted by Law No. 19.123 (PDF-254KB), January 31, 1992), as recommended by the Rettig Commission. Ongoing financial support has been provided for families of victims named in the commission's report, totaling approximately 16 million USD each year. The Corporation also continued investigations that the commission was unable to complete.

- The reparations program was limited by the fact that the Rettig Commission could not address victims of human rights violations outside of its mandate, including victims of torture that did not result in death or disappearance.

- Almost two decades after the release of the Rettig Commission’s report, the Chilean Congress passed Law No. 20.405 in November 2009, creating the Institute for Human Rights and re-opening the qualification of victims entitled to reparations (see also the Reparations section on the National Commission on Political Imprisonment and Torture).

Special Notes: All individuals who testified received follow-up correspondence signed by the president and a copy of the commission’s final report. In 1999, the Clinton Administration of the United States declassified intelligence documents that shed light on human rights abuses, terrorism, and other acts of political violence in Chile. The documents were made available on the Internet.

Sources:

- Cuya, Esteban. "Las Comisiones De La Verdad En América Latina." Ko'Aga Roñe'Eta iii, (1996): July 1, 2008. Available at http://www.derechos.org/koaga/iii/1/cuya.html (accessed July 1, 2008).

- Ensalaco, Mark. "Truth Commissions for Chile and El Salvador: A Report and Assessment." Human Rights Quarterly (1994): 656-675.

- Gairdner, David. Truth in Transition: The Role of Truth Commissions in Political Transition in Chile and El Salvador. Bergen: Chr. Michelsen Institute, Development Studies and Human Rights, 1999.

- Hayner, Priscilla B. Unspeakable Truths: Facing the Challenge of Truth Commissions. New York: Routledge, 2002.

- Peterson, Trudy Huskamp. Final Acts: A Guide to Preserving the Records of Truth Commissions. Washington, D.C.; Baltimore: Woodrow Wilson Center Press; Johns Hopkins University Press, 2005. Available at http://www.wilsoncenter.org/book/final-acts-guide-to-preserving-the-records-truth-commissions (accessed October 26, 2011).